The team at Murphy & Dittenhafer Architects expect to produce a final design for the building by spring, and construction should take about a year.

The creative minds at Murphy & Dittenhafer Architects conceive buildings that earn design awards and gain recognition for their energy efficiency.

But long before those honors can be bestowed, the Architects must understand the needs of the people who will use a building day in and day out.

That means asking the right questions to help a client visualize what is possible.

Architects Todd Grove and Jonathan Taube are one month into designing a new building for the Carroll County State's Attorney's Office. They have worked together very successfully on other M&D projects during recent years. In this case, Grove has supervisory responsibility for the work.

Like us on Facebook!

The OSA is the county’s chief law enforcement agency, prosecuting all criminal cases. It includes a Major Offender Unit, Special Victim Unit, Economic Crimes Unit, and county Drug Court. The office administers the county’s district and circuit courts.

When the agency sought proposals for a new building, Murphy & Dittenhafer stepped forward to demonstrate the firm’s qualifications and experience – and with a conceptual design for this type of new municipal facility. After an in-house conversation among the Architects about the nature of such a structure, Grove and Taube met with county officials, the prospective clients.

“At times, we will take in visuals, not because we have figured out a design for the new building but more so to demonstrate how we would work, the kind of conceptual drawings and images we can produce to help a client visualize a new facility,” Grove explains. “It’s more about establishing a relationship.”

“We usually provide them with a preliminary program,” Taube adds. “We take a shot at it to demonstrate our understanding of the program.” In this case, he says, “They were really receptive.”

Focusing on needs

After coming onboard with a client, the Architects meet with those who will use the building to determine their needs and how they work. In this project, for example, there must be private settings for sensitive conversations, as well as secure storage for evidence and documents.

“There is a Special Victim Unit that has special requirements,” Taube notes. “You need a hospitable feeling in that space, where children can be comfortable while their parents are interviewed.”

“We try to get out of them what their vision is for the project,” Grove says. “What do they think it should look like? It’s interesting how sometimes the initial sketch we show them is on target and an actual starting point” for creating several options.

“It’s really important to ask the right questions,” Taube says.

From those conversations, the Architects develop computer-generated schematic floor plans that lay out public and private spaces; suggest the location of offices, work stations, break rooms, doors, and windows; and address the need for expansion.

The OSA wants to locate its roughly 50 employees in one building, with updated information technology and data capabilities that it lacks at its current main site in downtown Westminister which has become crowded. One key need in the new three-story structure is a training room for regional workers.

The location of departments is important to the agency’s workflow.

“A department that interfaces with the public is better near the main entrance on the first floor,” Grove points out.

Attention to detail

The exterior of the building is another major consideration.

“We’re at a point in the design where we’re asking ourselves about what a state attorney’s office should look like in a historic town such as Westminster in a campus of existing county buildings with their own architectural styles,” Grove says. “We want the new building to look comfortable in its setting.”

The Architects will weigh the use of steel or masonry components, which might be decided by local building codes. The type of construction can affect elements of the design, Taube notes, including the location of stairways and sprinkler systems, or the length of a hallway.

Grove and Taube meet with County officials on a monthly basis to go over the developing plans and get feedback. Then they return to the “drawing board” to refine the design before reviewing it with County officials the next month.

The Architects expect to produce a final design for the building by spring. Construction, Grove says, should take about a year.

Still early in the process, some elements remain undetermined, such as a plan for employee and visitor parking. Those factors can affect the layout of a building, Taube explains.

“Sometimes,” he says, “this phase reveals the need to move things around.”

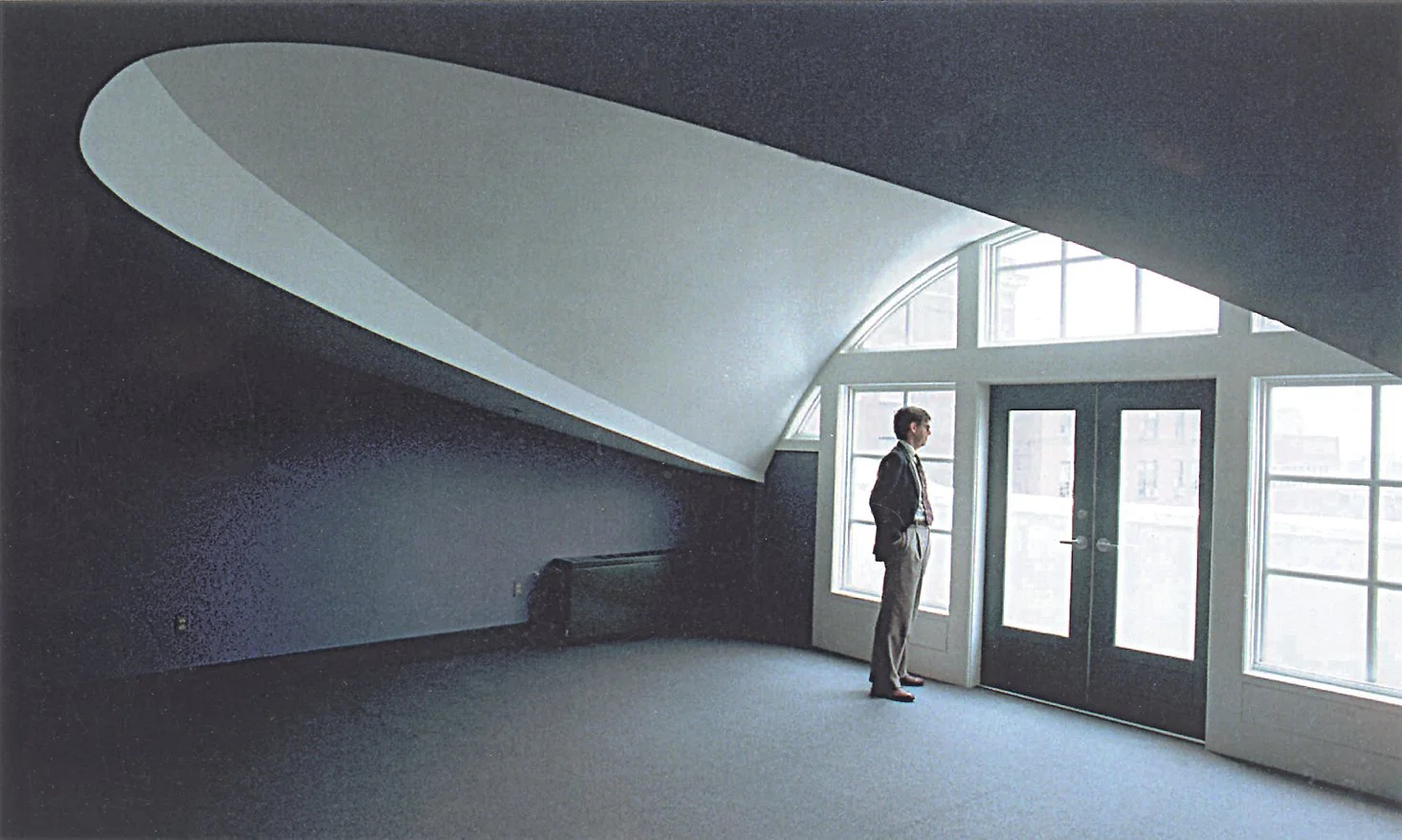

To round out our 40th-year celebrations, enjoy 10 more impactful and diverse Architecture projects designed by M&D. These projects, most of which have received design awards, confirm the variety in design (from scale to usage) that we continue to be involved in today.

Murphy & Dittenhafer Architects is working hard and collaborating with the community on an urban planning study for South George Street in York City.

“Historic preservation has always been a hallmark of ours for our 40-year history,” says M&D President Frank Dittenhafer II. These 10 projects exemplify our passion for this work.

It’s the 40th year of Murphy & Dittenhafer Architects, so Frank Dittenhafer II, President, is taking the time to highlight some of our most influential projects over the decades.

We’re celebrating 40 years of influence in Pennsylvania and Maryland. With that, we couldn’t help but reflect on some of the most impactful projects from our history.

Harford Community College’s expanded new construction Chesapeake Welcome Center is a lesson in Architectural identity

At Murphy & Dittenhafer Architects, we feel lucky to have such awesome employees who create meaningful and impressive work. Meet the four team members we welcomed in 2024.

The ribbon-cutting ceremony at the new Department of Legislative Services (DLS) office building in Annapolis honored a truly iconic point in time for the state of Maryland.

As Murphy & Dittenhafer architects approaches 25 years in our building, we can’t help but look at how far the space has come.

Murphy & Dittenhafer Architects took on the Architecture, Interior Design, & Overall Project Management for the new Bedford Elementary School, and the outcome is impactful.

The memorial’s groundbreaking took place in June, and the dedication is set to take place on November 11, 2024, or Veterans Day.

President of Murphy & Dittenhafer Architects, Frank Dittenhafer II, spoke about the company’s contribution to York-area revitalization at the Pennsylvania Downtown Center’s Premier Revitalization Conference in June 2024. Here are the highlights.

The Pullo Center welcomed a range of student musicians in its 1,016-seat theater with full production capabilities.

“Interior designs being integral from the beginning of a project capitalize on things that make it special in the long run.”

Digital animations help Murphy & Dittenhafer Architects and clients see designs in a new light.

Frank Dittenhafer and his firm work alongside the nonprofit to fulfill the local landscape from various perspectives.

From Farquhar Park to south of the Codorus Creek, Murphy & Dittenhafer Architects help revamp York’s Penn Street.

Designs for LaVale Library, Intergenerational Center, and Beth Tfiloh Sanctuary show the value of third places.

The Annapolis Department of Legislative Services Building is under construction, reflecting the state capital’s Georgian aesthetic with modern amenities.

For the past two years, the co-founder and president of Murphy & Dittenhafer Architects has led the university’s College of Arts and Architecture Alumni Society.

The firm recently worked with St. Vincent de Paul of Baltimore to renovate an old elementary school for a Head Start pre-k program.

The market house, an 1888 Romanesque Revival brick structure designed by local Architect John A. Dempwolf, long has stood out as one of York’s premier examples of Architecture. Architect Frank Dittenhafer is passing the legacy of serving on its board to Architectural Designer Harper Brockway.

At Murphy & Dittenhafer Architects, there is a deep-rooted belief in the power of combining history and adaptive reuse with creativity.

University of Maryland Global Campus explores modernizing its administration building, which serves staffers and students enrolled in virtual classes.

The Wilkens and Essex precincts of Baltimore County are receiving solutions-based ideas for renovating or reconstructing their police stations.

Here’s 10 unbuilt projects with designs we adore for all kinds of reasons.