“For the first time at night, you can see Old St. Paul’s Rectory,” says Murphy & Dittenhafer Architects’ Peter Schwab. “It’s a new and different thing for the city to have this old building back.”

(Photo by Jim Popa)

When renovating a historic building, sometimes history itself poses the biggest challenge.

After Murphy & Dittenhafer Architects of Baltimore and York, Pennsylvania, completed several projects at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Baltimore, the firm shifted its attention to the church rectory, a 1792 late Georgian/Federal-style brick house where two oversight agencies mandated a strict adherence to historical accuracy.

Architects Lauren Myatt and Peter Schwab found themselves playing history detectives as they researched the design elements at the 1856 church on Charles Street and the rectory on Saratoga Street.

“I thought we’d never get there,” Schwab says of the historical documentation required at the rectory.

A multi-faceted renovation

Several years ago, Myatt investigated the church’s wood ceiling and its layers of paint. Though she couldn’t determine whether painted stars adorned the original ceiling – a style popular in the mid-1800s – the church decided to repaint it a different shade of blue and add the stars.

She also fashioned a new paint and lighting scheme for the sanctuary, redesigned to add fellowship space, and repurposed a choir room to create extra classroom space.

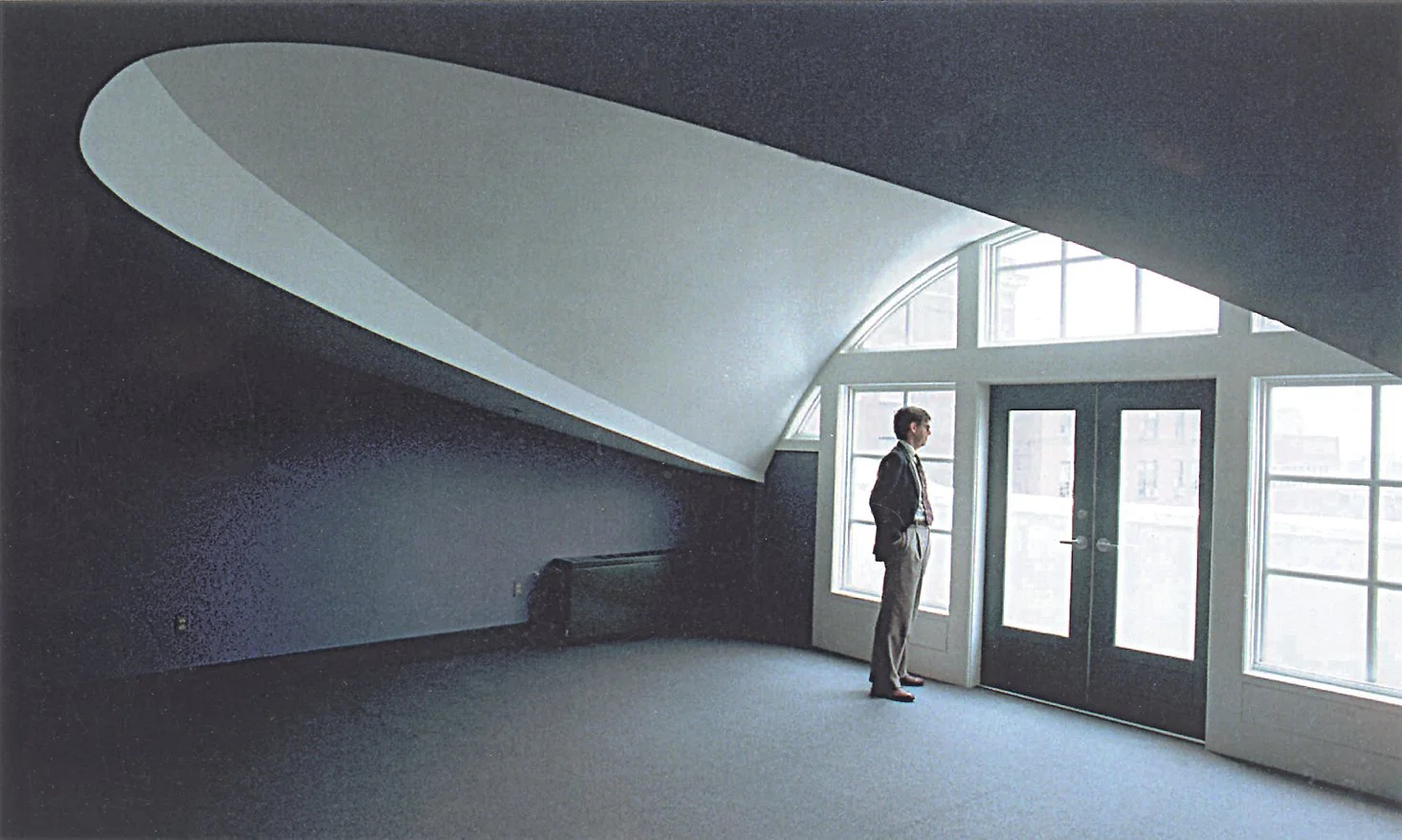

The three-story rectory had been the rector’s home until the 1980s and then was leased to outside organizations. The church recently decided to renovate it into office and meeting space that it needed. The structure, which Schwab says is one of Baltimore’s oldest buildings, features a partially cantilevered octagonal stair and rows of circular windows.

“Being a port town that expanded so fast, a lot of colonial structures were taken down or lost in the great fire of 1904,” Schwab explains. The Rectory is a survivor, and it holds a special significance for Schwab, whose ancestors were among the church’s original vestry, a committee that helped manage parish affairs.

Like us on Facebook!

Myatt redesigned the second floor as office space and the first floor primarily for group meetings. Where she could, she retained the original long-leaf or old-growth hard pine floors. Alabama pine was a source for replacement flooring.

The kitchen probably required the least adherence to historical standards because it had undergone other renovations. Now with new appliances, it can serve groups that meet at the Rectory.

“We still did need to follow historical guidelines when upgrading the kitchen in terms of its significant historical features,” Myatt says. “One was the original fireplace and hearth.”

Another requirement: The tin roof over the kitchen area with its crimped and bent seams, probably from the late 19th century, had to be maintained.

(Photos by Jim Popa)

Digging into history

As Myatt designed, Schwab researched historical specifications to satisfy the city’s Commission for Historical and Architectural Preservation (CHAP) and the Maryland Historical Trust. He had to find experts in specific elements of the rectory project.

The original plaster used horsehair as a binder, so replacement plaster had to include animal hair.

“We had a company originally from London that did the plaster restoration,” Schwab says.

The mortar used to repoint the brick exterior had to contain natural lime. The building has at least three layers of brick.

“All buildings did back then because they were structural walls,” Schwab points out.

The exterior work, which Myatt helped design, included repairing wood trim and installing energy-efficient storm windows.

In some cases, Schwab tried to get the Historical Trust to relent, such as allowing the removal of an old oak tree that could fall on the Rectory.

Following historical guidelines from roof to basement, the architects maintained a cobblestone cellar floor when a sump pump was installed. They also designed a new heating and air-conditioning system.

(Photos by Jim Popa)

A rewarding project

The work at the Rectory is nearly done, and Schwab says the formerly rundown building, with exterior up-lighting, sends a new message to Baltimore.

“For the first time at night, you can see Old St. Paul’s Rectory,” he says. “It’s a new and different thing for the city to have this old building back that they have not noticed for a long time.”

The final piece of the overall campus puzzle will be the addition of a ramp into the Church, which must comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act and not damage the entrance’s marble steps.

CHAP rejected the first design because it would have meant cutting into the original granite and marble steps. So, Myatt is tweaking her plan to protect the steps and fit the ramp into the available space.

Despite the challenges, the work at Old St. Paul’s has proved satisfying for the architects.

“Working with churches definitely adds another layer of sensitivity that needs to be considered,” Myatt says.

Schwab views designing for houses of worship as special.

“You’re working on a space that has a soul,” he says.

To round out our 40th-year celebrations, enjoy 10 more impactful and diverse Architecture projects designed by M&D. These projects, most of which have received design awards, confirm the variety in design (from scale to usage) that we continue to be involved in today.

Murphy & Dittenhafer Architects is working hard and collaborating with the community on an urban planning study for South George Street in York City.

“Historic preservation has always been a hallmark of ours for our 40-year history,” says M&D President Frank Dittenhafer II. These 10 projects exemplify our passion for this work.

It’s the 40th year of Murphy & Dittenhafer Architects, so Frank Dittenhafer II, President, is taking the time to highlight some of our most influential projects over the decades.

We’re celebrating 40 years of influence in Pennsylvania and Maryland. With that, we couldn’t help but reflect on some of the most impactful projects from our history.

Harford Community College’s expanded new construction Chesapeake Welcome Center is a lesson in Architectural identity

At Murphy & Dittenhafer Architects, we feel lucky to have such awesome employees who create meaningful and impressive work. Meet the four team members we welcomed in 2024.

The ribbon-cutting ceremony at the new Department of Legislative Services (DLS) office building in Annapolis honored a truly iconic point in time for the state of Maryland.

As Murphy & Dittenhafer architects approaches 25 years in our building, we can’t help but look at how far the space has come.

Murphy & Dittenhafer Architects took on the Architecture, Interior Design, & Overall Project Management for the new Bedford Elementary School, and the outcome is impactful.

The memorial’s groundbreaking took place in June, and the dedication is set to take place on November 11, 2024, or Veterans Day.

President of Murphy & Dittenhafer Architects, Frank Dittenhafer II, spoke about the company’s contribution to York-area revitalization at the Pennsylvania Downtown Center’s Premier Revitalization Conference in June 2024. Here are the highlights.

The Pullo Center welcomed a range of student musicians in its 1,016-seat theater with full production capabilities.

“Interior designs being integral from the beginning of a project capitalize on things that make it special in the long run.”

Digital animations help Murphy & Dittenhafer Architects and clients see designs in a new light.

Frank Dittenhafer and his firm work alongside the nonprofit to fulfill the local landscape from various perspectives.

From Farquhar Park to south of the Codorus Creek, Murphy & Dittenhafer Architects help revamp York’s Penn Street.

Designs for LaVale Library, Intergenerational Center, and Beth Tfiloh Sanctuary show the value of third places.

The Annapolis Department of Legislative Services Building is under construction, reflecting the state capital’s Georgian aesthetic with modern amenities.

For the past two years, the co-founder and president of Murphy & Dittenhafer Architects has led the university’s College of Arts and Architecture Alumni Society.

The firm recently worked with St. Vincent de Paul of Baltimore to renovate an old elementary school for a Head Start pre-k program.

The market house, an 1888 Romanesque Revival brick structure designed by local Architect John A. Dempwolf, long has stood out as one of York’s premier examples of Architecture. Architect Frank Dittenhafer is passing the legacy of serving on its board to Architectural Designer Harper Brockway.

At Murphy & Dittenhafer Architects, there is a deep-rooted belief in the power of combining history and adaptive reuse with creativity.

University of Maryland Global Campus explores modernizing its administration building, which serves staffers and students enrolled in virtual classes.

The Wilkens and Essex precincts of Baltimore County are receiving solutions-based ideas for renovating or reconstructing their police stations.

Here’s 10 unbuilt projects with designs we adore for all kinds of reasons.